The Brandywine Conservancy is a month away from releasing the final version of its Brandywine Flood Study, a plan with recommendations that will help keep people and property safe in the event of future flooding. That was the word from Grant DeCosta, the conservancy’s director of community services.

That study was spurred by the devastation from the September 2021 flooding from Hurricane Ida.

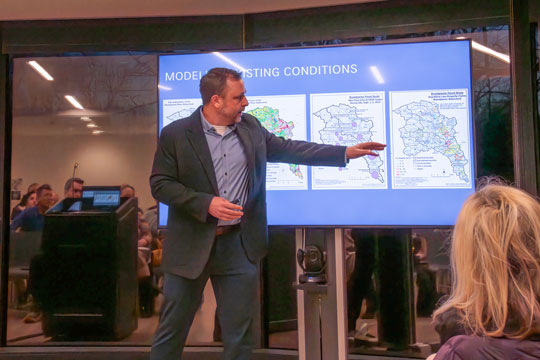

DeCosta spoke to a small group of people during a March 4 meeting held in a second-floor meeting room at the museum, saying that there are several approaches to mitigating flood damage before the damage is done, but nothing can prevent another Ida when the flood level reached 21 feet. By comparison, the next highest flood level was 17 feet during Hurricane Floyd in 1999. The volume of water from Ida, he said, was 46,000 cubic feet per second in Chadds Ford. Other areas had different flood volumes.

Prioritizing those recommendations is difficult at times, he said, because it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach, but there are some primary goals.

“I would say public awareness, and education so we can help people before, during, and after storms. Preventing further loss of life has got to be on top.”

He said there was one fatality in Downingtown because of the flooding from Ida.

The study has focused on what people and municipalities can do to both raise awareness and protect lives and property. Those measures include structural and non-structural means.

Non-structural means include legislation on municipal and county levels — where and how to build or not depending on location — open space requirements, and rules set up by homeowners’ associations, among others.

Structural means include improving the functionality of dams, flood plains, and culverts where necessary. Also included are improvements and enhancements to stormwater basins.

But prioritization is difficult, however, because it’s a matter of different approaches for different locations.

DeCosta said prioritization is “a hard struggle for us. We’ve had many discussions with the study team and with our advisory committee of 60-plus individuals, [asking] ‘How would you do a prioritization?’ And that’s where we struggled.”

He explained that different areas have their own priorities, timing, and topographical considerations. The type of project also plays a part in prioritization.

“A land preservation project is typically a different timeline, has a different funding source, and is a different organization than making sure that there’s some operation or maintenance happening at some stormwater basin that didn’t have it before. They don’t need to compete against each other. Different organizations and municipalities have their own priorities.”

As an example, he said Chester County wants to move forward improving Barneston Dam — a flood control dam along the East Branch of the Brandywine in Wallace Township — but Chester County also is robust regarding open space programs that can also work to lessen the chance of a major flood damage.

Seung Ah Byun, the executive director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority added that some areas need to address aging infrastructure, such as culverts that need to be replaced or “right-sized” to help reduce the flooding problem.

In all, DeCosta said after the meeting, the aim is to help people protect themselves and their property before and during a flood event and help them recover after such an event.

One of the things learned from people making comments during the study is that many people don’t have flood insurance. Only about 23 percent said they have flood insurance while 95 percent are worried about future floods, 51 percent have experienced property damage and 66 percent have experienced financial loss due to flooding. Flooding also caused travel difficulties — getting to work or getting essential services — for 79 percent of those commenting.

Virginia Logan, the executive director of the Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art, said the meeting is part of the conservancy’s effort to raise awareness and help keep people safe.

“The combination of education awareness and emergency procedures is vitally important. And I think the other part of it is, ultimately, you’re going to find that each municipality or each localized area will have some insights that are reflected in the study, and that’s going to differ from area to area,” Logan said.

While the time period for public comment ended officially on March 1, DeCosta said people can still comment and read the latest draft of the study on the conservancy’s website.

Again, the final report is due in early April.

About Rich Schwartzman

Rich Schwartzman has been reporting on events in the greater Chadds Ford area since September 2001 when he became the founding editor of The Chadds Ford Post. In April 2009 he became managing editor of ChaddsFordLive. He is also an award-winning photographer.

Deprecated: Automatic conversion of false to array is deprecated in /var/www/vhosts/chaddsfordlive/public_html/wp-content/plugins/wp-postratings/wp-postratings.php on line 111

Deprecated: Automatic conversion of false to array is deprecated in /var/www/vhosts/chaddsfordlive/public_html/wp-content/plugins/wp-postratings/wp-postratings.php on line 1213

Comments