I love a good story. Indeed, the more challenging my life, my work, or the world around me seems, the more I seek out stories. In quiet moments, I will read a book–fantasy, thriller, sci-fi, even romance–to explore an alternate world and perspective. In my career, I go out of my way to hear people’s personal stories, letting their experiences expand my perspectives.

So here is a story that leads to a re-reading of a story: In my final year of rabbinical school, I was required to take a class in homiletics. The word alone should tell you that there were high expectations of what turned out to be advice on how to give a good sermon. Seeking to learn a broader view of sermonizing, I chose to take a homiletics class at the Christian seminary across the street. While I still remember many of the lessons learned in that class, one keeps coming back to me: try telling the Scriptural story from the perspective of a less obvious character.

When I chose to tell the story of the Ark of the Covenant, as if it was a young woman, my classmates and I had a great deal to unpack. Theologically, they were shocked by the idea of giving human voice to an inanimate object, especially when that human voice stood in for the Divine view during parts of my sermon. We laughed about the Jew in the class believing in a form of incarnation. And then we learned from having to do that unpacking how easy it is to be caught in our own story and to miss the story of those around us. I was trying out a sermon technique to make a case for making room for God; they were being challenged to see their acceptance of God becoming human as an opening for theological ideas I never intended.

In two weeks, Jews will celebrate Purim, the holiday commemorating the story found in the Book of Esther. This year, the story haunts me as a tale of antisemitism, which I wrote about here two years ago. So, this year, I wondered what else the story might tell me, what might challenge me to see something else, and I used that homiletical device to find a quiet voice.

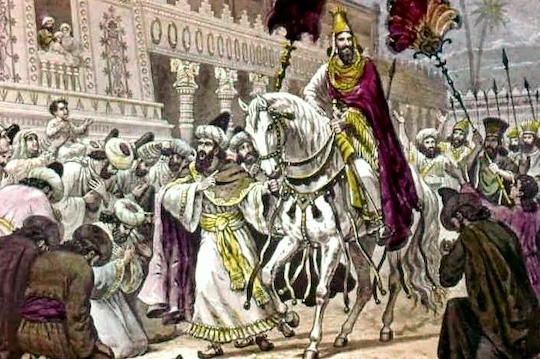

I wondered about the groom who had to lead King Achashverosh’s horse with Mordechai riding, instead of the king’s highest minister Haman. Was the groom worried Mordechai would not know how to ride? What did the groom think of this newly honored Jew in a moment of court intrigue? And what did all the onlookers think? What if one of the onlookers was a Jewish shopkeeper? What did the groom or the shopkeeper talk about at their dinner tables that night with their families?

I truly believe that Scripture includes the names of minor figures (and ritual objects) to remind us that there is more to the story than the protagonist, antagonist, and other leading roles. Yes, Esther, Mordechai, Haman, Queen Vashti, and King Achashverosh tell a central story of Jews both hiding their identity and standing up for it in the face of hatred. They were not the only ones in the story, though. There were others who took sides, and there were those quiet voices I mentioned, too.

I imagine those quiet voices saying things like “I saw the world turned upside down today;” “I never imagined such different peoples could be equally honored;” and “I did my job well today; even with Haman leading, the saddle held Mordechai.” Those voices, those experiences tell us of the quiet drama of seeing our deeper humanity, maybe even God’s image made audible in their quiet conversations. May we listen to those voices and not just the loud ones; the quiet ones echo beyond any chamber.

About Rabbi Jeremy Winaker

Rabbi Jeremy Winaker is the executive director of the Greater Philadelphia Hillel Network, responsible for West Chester University, Haverford, Bryn Mawr, and other area colleges. He is the former head of school at the Albert Einstein Academy in Wilmington and was the senior Jewish educator at the Kristol Hillel Center at the University of Delaware for four years. Rabbi Winaker lives in Delaware with his wife and three children.

Comments