This coming Monday is a significant day in history. Not because it’s Labor Day, but because Sept. 5 is Jury Rights Day. What few people realize is that jurors have the right to find a defendant not guilty even if the accused is guilty of the charges. And some of our constitutional guarantees — freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and press — are rooted in that fact.

Sept. 5 is Jury Rights Day because it was on that date in 1690 when William Penn and William Mead were prosecuted for unlawful assembly, disturbing the peace, and rioting. What had they done? They preached to a meeting of several hundred Quakers.

Sept. 5 is Jury Rights Day because it was on that date in 1690 when William Penn and William Mead were prosecuted for unlawful assembly, disturbing the peace, and rioting. What had they done? They preached to a meeting of several hundred Quakers.

The jury only found them guilty of speaking to an assembly. Not surprisingly, the judge didn’t like that limited guilty verdict and ordered the jury to return to its deliberation. When the jury returned with a full acquittal, the judge imprisoned the jury. The jury filed a writ of habeas corpus and was eventually freed. So were Penn and Mead. The jury invalidated an unjust application of the law. It’s called jury nullification.

Jury nullification showed up again 45 years later in colonial New York. John Peter Zenger, a journalist, was tried for libeling William Cosby, New York’s royal governor. Zenger did indeed print libelous comments about Cosby, but the jury returned a verdict of not guilty.

Similar results came in the wake of failed prosecutions for people guilty of violating the Alien and Sedition Act in the early 1800s. And in the mid-1800s, juries used their power to acquit people who had violated the Fugitive Slave Laws.

And again, in the 1930s, juries practiced nullification in cases brought against people charged with violating alcohol control laws.

Perhaps nullification is an awkward word in this situation since the law itself is not nullified. The law still stands, but the application of the law is nullified in that specific case.

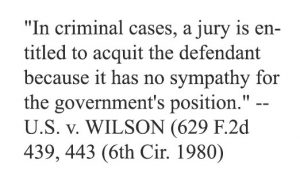

As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes said in Horning v. District of Columbia, 249 U.S. 596: "The jury has the power to bring a verdict in the teeth of both law and fact."

But Holmes was just echoing what John Jay, the first Supreme Court chief justice, said in 1794: “The jury has the right to judge both the law as well as the fact in controversy.”

Jurors are usually unaware of this right and power because judges and prosecutors don’t like it. It intrudes into and impinges on their power. So, they don’t tell jurors about it, and a defense attorney could catch hell from the judge if he or she brought it up. It’s pure speculation, but women could conceivably have had the right to vote almost 50 years sooner had jurors known about their right to nullify.

Susan B. Anthony, along with 14 other women, went on trial for illegal voting in the 1872 election. It was against the law for women to vote in New York. They clearly had voted despite the law, but the jury wanted to acquit. The defense attorney wanted the jurors to know their rights. But Justice Ward Hunt wouldn’t allow that and ordered a directed verdict. One wonders what might have happened had Anthony been acquitted.

The Supreme Court ruled in the 1890s that judges were not required to advise jurors of their right to acquit despite the facts, but the right still exists. Judges might not be compelled to tell jurors of their rights, but the decision doesn’t deny the right.

Consider this from the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, U.S. v. Moylan, 1969:

“If the jury feels the law is unjust, we recognize the undisputed power of the jury to acquit, even if its verdict is contrary to the law as given by a judge, and contrary to the evidence.... If the jury feels that the law under which the defendant is accused is unjust, or that exigent circumstances justified the actions of the accused, or for any reason which appeals to their logic or passion, the jury has the power to acquit, and the courts must abide by that decision.” [Emphasis added.]

While it may be intuitive to say that someone who violates a law should be found guilty and subject to punishment, what happens if the law is wrong, outdated, or unjust? What if the law is political in nature or there is no victim? Does a juror turn off his or her moral compass, their sense of right and wrong, because a judge says so?

So, as you grill on the unofficial last day of summer, consider the significance of Sept. 5 and the significance of having jurors fully informed of their rights.

About Rich Schwartzman

Rich Schwartzman has been reporting on events in the greater Chadds Ford area since September 2001 when he became the founding editor of The Chadds Ford Post. In April 2009 he became managing editor of ChaddsFordLive. He is also an award-winning photographer.

Comments