Most people have undoubtedly cooked a steak at one point or another. Some are grilling gurus and some can cook a run-of-the-mill ribeye. Other people people don't know the difference between raw and well done. No one should be too intimidated to try new things. A steak, properly cooked, can take dinner from edible to extraordinary.

There are only a select few tips that one needs to know to have a steak turn out great, but it all begins with picking the right steak. There are so many cuts to choose from. Some are more tender, others are more flavorful and there are even those that are best when shared.

Classic cuts, such as a ribeye or NY Strip, are well known for their incredible flavor and visual appeal. A well-cut steak of these types should be between an inch and a quarter and an inch and a half thick. This is the optimal thickness to allow for the full spectrum of “doneness” options.

(Steaks cut thinner than this have a tendency to approach well done without allowing for both a well-developed crust and tender, juicy interior.)

Depending on the size of the loin these steaks are cut from, this could result in steaks that are nearly a pound each, or even more! These steaks also make for great shareable meals, with many great possibilities for leftovers. Cheese steaks anyone?

If one is looking for a more tender or smaller portioned cut, then the tenderloin (or filet, as many know it), hanger steak or butter steak (a deliciously flavored steak from the chuck) may be the solution. These options offer quicker cooking times and melt-in-your mouth goodness.

If one is looking for a more tender or smaller portioned cut, then the tenderloin (or filet, as many know it), hanger steak or butter steak (a deliciously flavored steak from the chuck) may be the solution. These options offer quicker cooking times and melt-in-your mouth goodness.

When shopping for a filet, thickness is even more important. Filets should be cut at two to two-and-a-half inches, and when buying multiple filets it very important to make sure they are all of consistent thicknesses, rather than overall weight. A six-ounce filet and an eight-ounce filet cut to a similar thickness will cook at much closer rates than two eight-ounce filets cut at very different thicknesses.

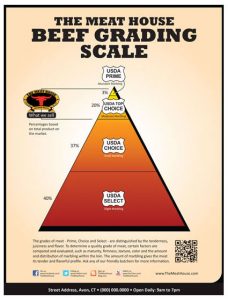

Now that the cut has been decided on, it’s time to head back to school and focus on the grade. The USDA grades beef into eight different categories, the two most important ones to remember are (prime and choice), but it’s also good to know about a very common one (select) that can generally be found in superstores and mega-marts because of their low price point.

These grades come down to one thing: fat. Not the chewy, chunks of fat some people identify with dishes like prime rib. We’re talking about the delicious, melt away while it cooks and adds tons of flavor kind of fat called marbling — the delectable white flecks found in the middle of the meat (aka: lean). The more marbling, the more flavor and the higher grading it will receive.

The USDA qualifier in USDA Prime or USDA Choice is also an important distinction. Some places will do an “in-house grading.” On the package, they will include a phrase such as “Prime Cut” (not prime grading) or in small print “Compare to” above a larger font word “Choice.” It is designed to make the consumer think they are buying a higher quality cut. Knowing the range and quality of meat that is being sold, is an important piece of knowledge to have. Look for the USDA label; go to a local specialty butcher shop; ask questions.

There are also aging methods that can be kept in mind when choosing a steak. The common, and ever prevalent wet-aging — the process of vacuum packing sections of beef and letting the aging occur for four to ten days between processing and the market — accounts for upwards of 90 percent of all the meat sold in the United States. It’s preferred because there is little waste and loss, along with being the taste most everyone is familiar with.

Dry-aging, a traditional but rarely used method of placing sections of beef in a temperature and humidity controlled room for an average of 30 days, creates a piece of meat, known for its intense flavor and incredible tenderness. This method makes for an enjoyable steak; but at a cost, literally and figuratively. There is about a 30 percent loss of water content, which in turn means less yield, which then, in turn, means it tends to cost quite a bit more than for a wet-aged steak in the same grade.

Now the cut has been picked, the grade has been made and aging has been determined, it’s on to the fun parts: cooking and eating. All the things to know about the proper ways to prepare, cook, and serve a steak coming in Part II.

Eating may be a necessary part of life, but we might as well enjoy every bite.

Comments